The JA Ranch and Montie Ritchie

A talk given by Alex Hunt, Director of the Center for the Study of the American West, at the Amarillo Museum of Art February 23, 2017

Cornelia Adair

In January of 1915, Cornelia Adair

departed from the JA Ranch, rode the trains to New York, and

sailed January 30 for Liverpool, England on the R.M.S. Lusitania. On

May 7, 1915, the Lusitania was sunk by a German U-Boat torpedo,

killing 1,200. “Poor

Lusitania,,” Cornelia lamented to her ranch manager Timothy

Dwight Hobart.[1]

The Lusitania

incident brought worldwide condemnation against the Germans and

urged the US further toward joining the war effort. Cornelia,

accustomed to making an Atlantic crossing annually, was

heartbroken at being kept so long from the ranch. She noted that

it was especially hard for women to obtain permission to make

the crossing. Still, as she wrote in April of 1917, she was

“thrilled by America’s declaration of war” which she considered

overdue. She expected the Wadsworth men, in keeping with family

tradition, would be joining up forthwith.

At this time, Cornelia’s grandson, Montgomery Harrison Wadsworth Ritchie, was a four- or five-year-old residing in England. He remembers of that period once disturbing his grandmother Cornelia in her room, catching her without her wig on. His transgression earned him a spanking with her hairbrush.

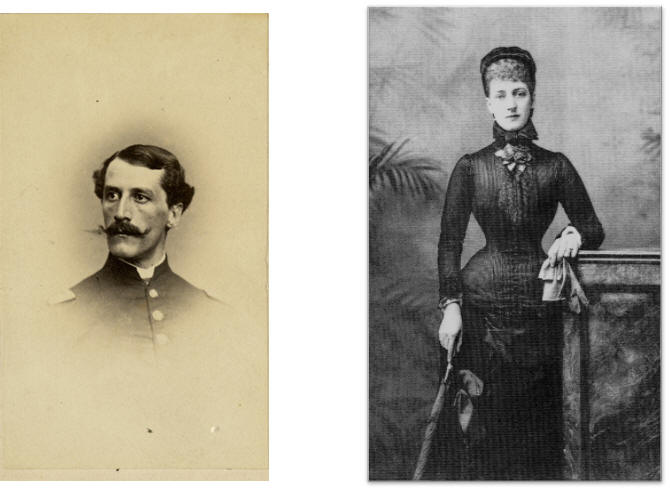

Montgomery Ritchie, ca. 1864

Cornelia was a great lady, a

Wadsworth of the illustrious Geneseo, New York family, her

father the Civil War General James Samuel Wadsworth. In 1857,

Cornelia married Montgomery Ritchie, who died of illness

incurred during his Civil War service. They had two sons, the

younger of whom, James Wadsworth Richie, known as Jack, would be

father to Montie Ritchie, whom we are honoring here this

evening.

Cornelia Adair, Bellegrove, Ireland

The widow Cornelia Ritchie remarried, choosing an Irish

landowner and financier John George Adair. The couple moved

between Ireland and the US. John Adair and Cornelia made an

adventurous tour of the western prairies in 1874, and

subsequently Adair was introduced to Charles Goodnight. The

great JA Ranch was formed in 1877, when Goodnight and Adair

signed what would be a lucrative contract. Demonstrating her

mettle, Cornelia rode horseback along with her husband and

Goodnight from Colorado to the new ranch. This partnership would

start a trend in British investment in Panhandle ranches and of

English financial adventurers in the western cattlelands, though

these were seldom as successful as was the JA. There’s an old

joke: He came to Texas with just 20 pence to his name—after five

years he had a million dollars debt—what a country!

When Adair died in 1885,

Cornelia continued the partnership with Goodnight. And when

Goodnight wished to end the partnership, Cornelia continued on

as owner of the JA—heavily involved in its management—until she

died in 1921.

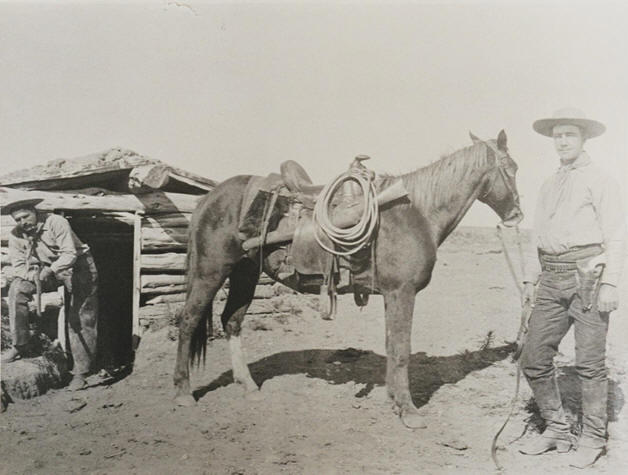

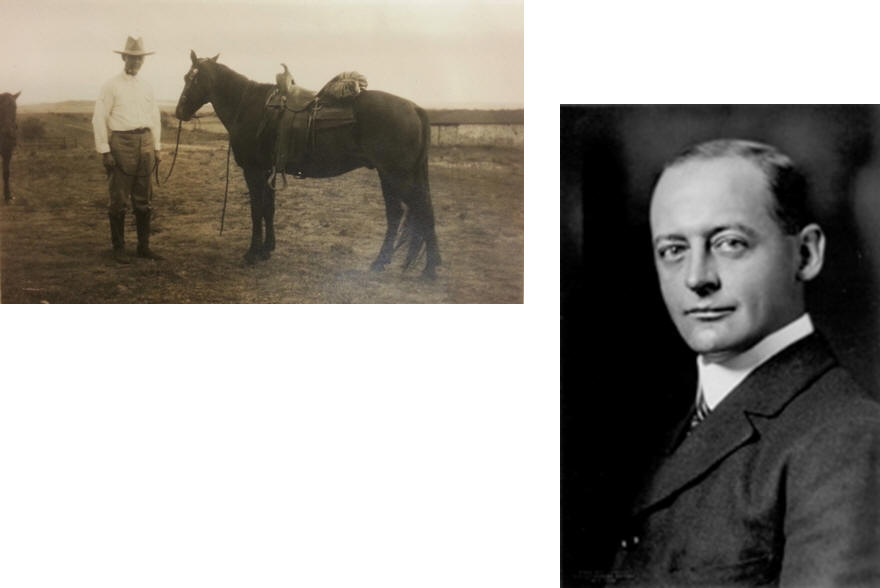

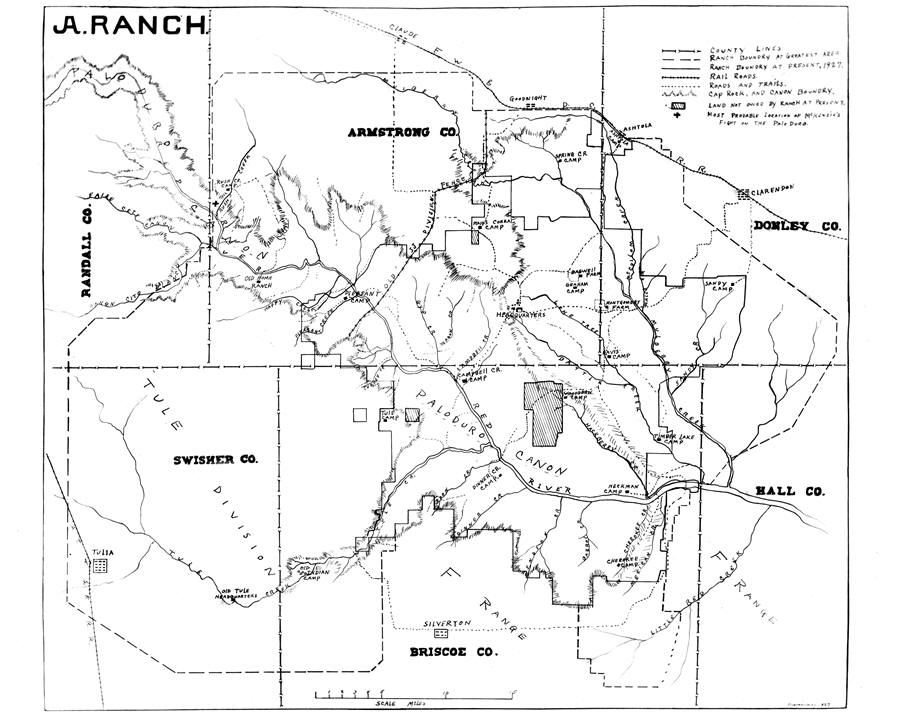

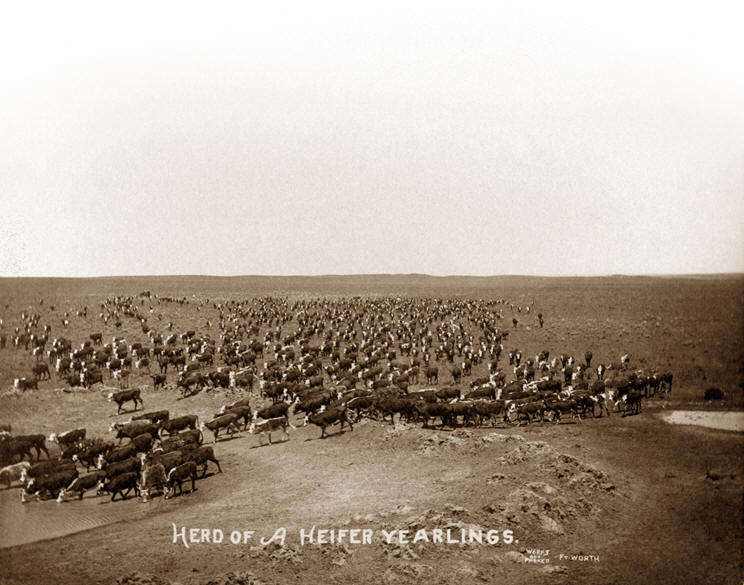

Jack Ritchie and Dick Walsh, ca. 1887

Cornelia’s son Jack came to the JA in

1887, working as a cowboy under Goodnight’s management. This was

at the apex of the JAs vast acreage.[2]

Jack soon became the manager of the Tule division, but by 1888

Goodnight demoted him for drinking and gambling with the

cowboys—Jack soon left the ranch, probably at his mother’s

urging. He went to work as a horse-buyer for the New York

Police, purchasing JA horses.

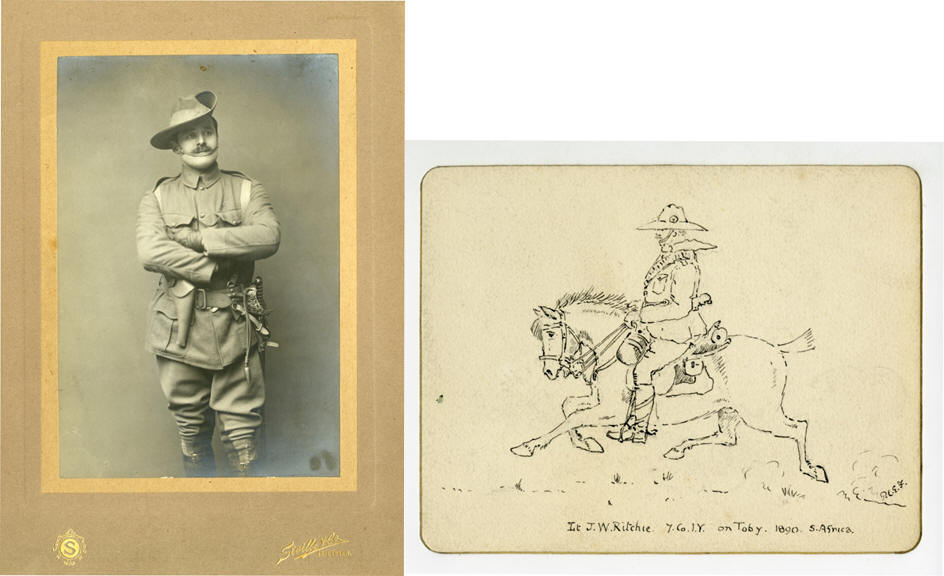

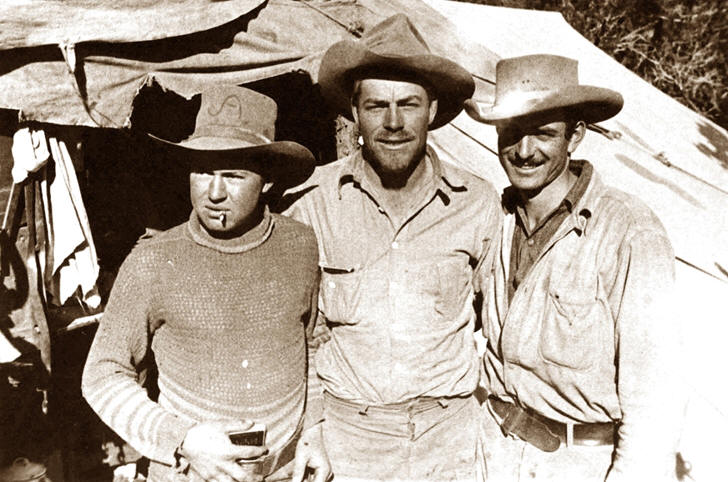

Jack Ritchie, Boer War, 1899

At the outbreak of the Boer War, he

fought with the Leicester Yeomanry in South Africa, where

reportedly the skills with horses practiced at the JA served him

well. Jack died young, in fact just a few years after his

mother, in 1924. But his nostalgia about his time at the JA

influenced his son Montie (born 1910), who said “It was my

father’s stories that did it. He talked to me about the ranch

for 12 years. He said the time spent there was the happiest of

his life.”[3]

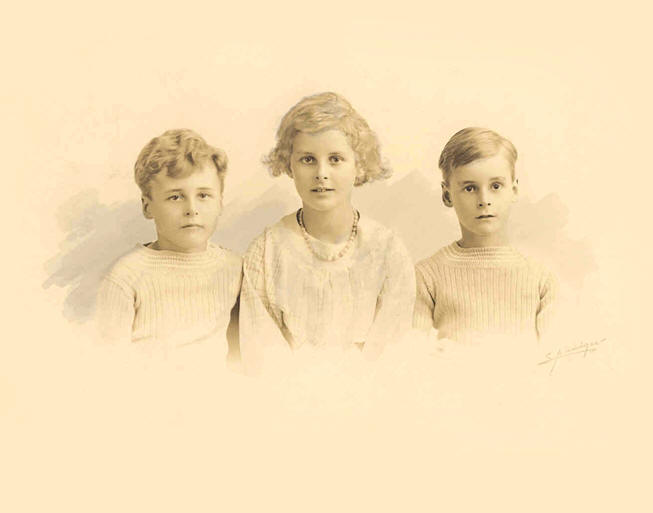

Richard, Gabrielle and Montgomery H. W. Ritchie, 1919

Freshly graduated from Cambridge

University, where he studied English Literature and History,

Montie Ritchie came to the ranch in the autumn of 1932. At this

time, the complex estate of Cornelia had not been settled

because the economic and environmental conditions of the

Panhandle prevented the sale of the JA. Ritchie came to learn

ranch work and out of curiosity born of his father’s stories.

But as one of Cornelia’ heirs, he was also most

interested in the condition of ranch and the situation of his

legacy. He later explained, “As heirs, we had received nothing

in payment of our legacies during the ten years since my

grandmother’s death, and I wanted to see our inheritance. I was

looking for adventure too, just as my father had. I found it. I

really can’t say that I came to stay on that first trip. Who

knows? I think I was more interested in seeing the ranch because

of what my father had told me.”[4]

Along with his elder sister Gabrielle and younger brother Dick,

Montie was a one of the beneficiaries of Cornelia Adair’s

estate.

Following Cornelia’s death in

1921, it was abundantly clear from her will and its codicils

that she expected that the sale of the JA would be necessary to

satisfy the legacies of her estate. She was, at the time of her

death, cash poor, in debt, and—where the JA was concerned—facing

a poor cattle and land market.

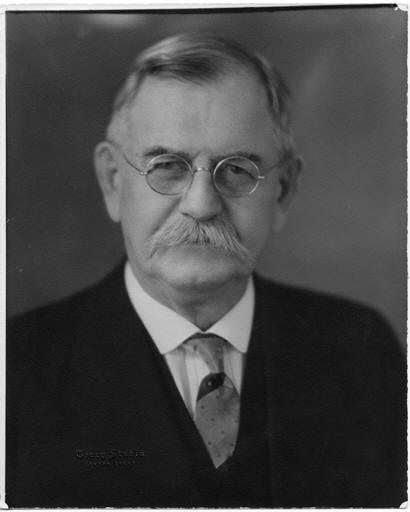

T. D. Hobart, ca. 1920

As dictated in her will, her estate

was managed by T. D. Hobart, manager of the JA since 1915, and

Henry Coke, Cornelia’s long-time Dallas lawyer. From 1921 to

1935, these men entertained many offers for the JA while

overseeing the ranch’s management. From the outset, conditions

for a sale were terrible -- depression and dust bowl of course made

them far worse. One report shows cattle prices slid from $45 a

head for calves in 1929 to $27.25 in 1930[5]--and

kept sliding. Hobart and Coke explained to Cornelia’s inheritors

that they must wait for more favorable financial conditions

unless they would accept a far reduced figure.

Hartford House, Geneseo, NY

Having arranged with T. D. Hobart a

job working on the ranch, Ritchie took his time getting

there. Following his steamship passage, he went to Geneseo to

visit his New York cousins. Cousin James W. Wadsworth Jr. was

particularly important. He had been Cornelia’s manager on the JA

from 1911-1915, leaving the ranch to become US Senator from New

York, a position he held until 1927 (US Congress, 1933-51).

Ritchie later remarked that over time, Wadsworth “gave me a lot

of advice on how I should approach the ranch, what I should do,

and how I should behave, all of which was very valuable to me.”[6]

James Wolcott Wadsworth, Jr.

This relationship was indeed essential, as James Wadsworth

advised Ritchie throughout the several years long period of

Ritchie’s assumption of control of the JA. Departing New York,

Ritchie’s voyage then proceeded by steamship across the Great

Lakes and then by train to Pampa. Here, met by Hobart, the two

took the train to Panhandle, then drove to the JA.

Expecting a job riding the range and

working cattle, Montie Ritchie—joined by his brother Dick—was

disappointed to be handed a shovel and put to work digging a

waterline from Mitchel Peak to the headquarters. “Eventually,”

Ritchie says, he and Snooks Sparks were assigned riding jobs.

Ritchie says he was given a “pretty fancy mount of horses” that

were given to “buck and run off”—“the idea seemed to be to

rather discourage

me staying with the wagon and punching cows, which is want I

wanted to do.” He did stick with it over several years,

remarking, “over the years I learned much more about operating

the ranch and taking care of the cattle and maintaining the

improvement of the ranch from the cowboys that I associated with

and made great friends with, than I did with the people who were

actually supposed to be managing the ranch. I think it was a

very valuable starter made.”[7]

JA Ranch Headquarters, 1903

Henry Coke died in 1932, leaving

Hobart as sole executor. Ritchie was soon convinced that Hobart,

now in his late 70s, was mismanaging the operation. He was

particularly critical of Hobart’s superintendent, Clinton Henry,

who became Ritchie’s nemesis. In particular, bolstered in his

views by James Wadsworth, Montie was convinced that the ranch

had been mismanaged in many ways, notably that too many of the

JA’s cows had been sold off, the horse herd was too large, and

the feed bills were wildly out of keeping with herd size and

market prices on feed. The administrative fees paid to Hobart

also seemed extravagant. Meanwhile, of course, in the depths of

the depression and drought, conditions were wretched; Ritchie

described “cattle . . . selling at $3 per calf, and the cattle

market . . . ruined.”[8]

Moreover, as a matter of political principle, Hobart had refused

to take advantage of New Deal agricultural programs like the

Drought Cattle Purchase Program.[9]

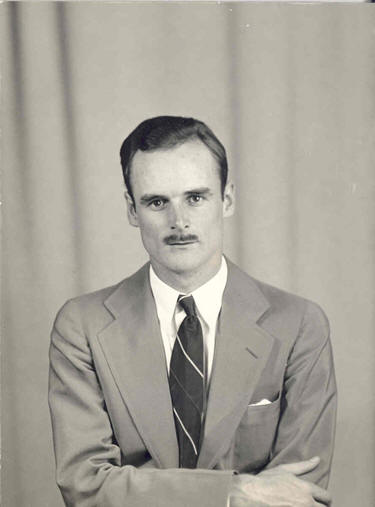

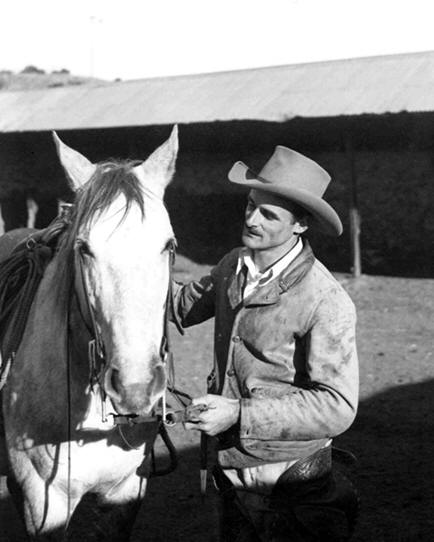

Montgomery H. W. Ritchie, 1937

Clinton Henry had refused Ritchie’s request to examine the

ranch’s account books, and Ritchie resorted to espionage. He

befriended the book keeper, a woman named Lottie Lane, and she

would periodically slip him the key for his afterhours

accounting work. I don’t know anything about Lottie Lane, but

her notes to young Montie suggest devotion to the handsome

Englishman. She related contents of letters dictated to her by

Hobart. She reported on visitors to the ranch, what cattle they

bought, what land they were considering. She reported on Clinton

Henry’s management difficulties and his increasing paranoia

about Ritchie’s presence. The ranch was the scene of a great

palace intrigue. Soon enough, Ritchie’s forensic accounting

endeavors were discovered. Lottie Lane was fired, Hobart ordered

Ritchie off the ranch.

For three years, then, Montie Ritchie based himself in Dallas

and Fort Worth hotels and waged a campaign against Hobart and

Henry. As the depression and drought continued, feeling

pressured from all quarters, Hobart pushed for the sale of the

ranch. Montie Ritchie, understandably, was concerned that Hobart

would sell out too cheaply just to be done with it. Ritchie

consulted with James Wadsworth, by this time a member of the US

House of Representatives, as well lawyers George Thompson of

Fort Worth and William Greenough of New York, about discouraging

an ill-advised sale.

James Wadsworth, agreeing with Montie

Ritchie’s assessment of poor management and high administrators’

fees instructed Ritchie to return to England to win the legatees

to his side. Wadsworth, fearing a messy family lawsuit, took a

not-so-subtle approach to influencing the situation from his

position in Congress. In April 1933, as Montie Ritchie returned

to England to enlist the British legacies, Representative

Wadsworth sent Hobart a telegram, which read: “Monty consulted

me before sailing. Please forgive my impertinence but in view of

program of Administration relating to currency etc etc, think

better go slow with any sale of land or cattle. These are

strenuous times. Regards”—JWW.[10]

The Congressman thus perhaps bought his second-cousin some time.

Importantly, Ritchie succeeded in gaining power of attorney from

most of the English legatees, including his mother and siblings

and Thomas Renshaw, Cornelia’s godson. He then returned to Fort

Worth to resume his campaign. He continued to take council from

James Wadsworth, as well as from former JA employee J. W. Kent.

He made continual requests of Hobart for information on the

ranch—as he was entitled to do—hoping to tire the old fellow

out. At one point, he even met with Hobart and made an initially

successful negotiation of convincing Hobart to retire. But

Hobart seemed determined to continue his efforts to sell the JA

and settle the estate.

In a letter to his Aunt dated July 10,

1933, Ritchie reported: “I hear disturbing news from the Ranch,

that some of the hands are getting out of control of Clinton

Henry in a demonstration in our favour. Brother Dick reports

that the general feeling out on the Ranch and in the

neighborhood is very strongly pro-legatee, which is very

comforting news.”

Also, as he continued, “I have received a letter written

anonymously warning me not to come near the ranch, which is

quite exciting and makes the whole thing sound rather like a

western novel, but I am not inclined to set much store by it.”[11]

Still, Hobart stubbornly held out. In

fact, in January 1935, Hobart wrote J. Evetts Haley—then at the

University of Texas in Austin—asking the young historian to

write “a short article” on the history of the JA for the

“Saturday Evening Post or some other magazine” that might gain

“the attention of the public and indirectly help us with a sale

to the government.”[12]

This sale obviously never occurred, but the episode seems to

underline Hobart’s desperation as Ritchie was pressuring Hobart.

In the end, T. D. Hobart died of pneumonia, dust pneumonia it

would seem, in May of 1935 at age 80.

Hobart’s family blamed Montie Ritchie

for Hobart’s death and asked him not to come to the funeral.

Clinton Henry barred Ritchie from the ranch and made an attempt

to have himself declared Estate administrator.[13]

Armed with powers of attorney and good legal help, though,

Montie was victorious, declared temporary trustee of the Adair

estate in September 1935.[14]

But he could not rest. Ritchie had to act decisively, for the ranch was heavily in debt, the situation dire. Ranch employees and former employees who had been loyal to Hobart remained opposed to Montie, hoping to see him fail, notably Clinton Henry. In Henry’s correspondence with J. Evetts Haley, also a Hobart loyalist, the two never refer to Montie by name, using euphemisms like “the young hopefull.”[15] Haley sought to gain intelligence for a would-be buyer of the ranch during this vulnerable period. Before proceeding to ask for detailed information about land and cattle, quantities and conditions, Haley explained that he’d been solicited by parties whom he’s “anxious” to accommodate, and remarked, “I understand that the young scissorsbill still hasn’t made bond. Do you think the place could be bought for $2,000,000 now, including the cattle?”[16] Henry reports back to Haley, whether or not “the Englishman . . . will make any special effort to sell the property right now I am unable to say, but it is my opinion that he will want to demonstrate his ability as a big cow man for awhile before he tryes to sell.”[17]

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, Ritchie retained Beale Queen as manager and Bill Beverly as wagon boss, but fired a number of cowboys he deemed disloyal or lazy. Snooks Sparks tells the story that one cowboy whined at his firing: “I didn’t do nothin”—replied another: “That’s why he fired you.”[18]

Fortunately, Montie Ritchie found strong support in Armstrong County Judge Charles Stewart, who was appointed as the court authority to oversee Montie’s handling of the estate.[19] Montie also had able help from attorney George Thompson, who negotiated a loan against 380,000 acres of the JA from the Southwest Life Insurance Company of Dallas—this loan at 5%, no interest due for 10 years. This money went toward the $365,000 in the ranch’s outstanding debt—a matter separate from the million owed to Cornelia’s legatees.

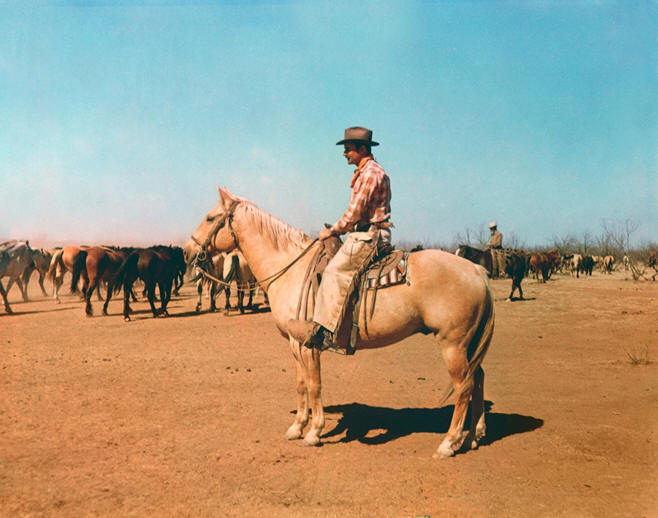

Montie Ritchie, J. W. Kent, Faye Kent and $4,000 bull 1938

By September of 1935, Montie was named permanent administrator of the Adair Estate, making him the official manager of the JA at the same time. He hired his ally and former JA employee J. W. Kent as superintendent. He also rehired bookkeeper Lottie Lane. Together, they got back to work producing high quality Hereford calves. It seems fair to say that he enjoyed ranch management more than working on Cornelia’s estate. He remarked, “Mrs. Adair’s will was an extremely complex instrument, and the local [Texas] attorney after reading it said he thought that every few pages the English attorney who wrote the will went off and got a drink, then came back and wrote some more at random and then repeated the process by getting another drink, so the will in its final form was very disorganized and difficult to follow.”[20]

Even though Montie had, to use Haley’s

term, “made bond,” he was by no means out of the woods. While it

seems the case that Montie Ritchie by this point hoped and

intended to preserve the JA, his obligation to other legatees

obligated him to take seriously offers made to purchase the

ranch. He showed the property to prospective buyers and came

very close to selling the ranch to the federal resettlement

bureau as an agricultural and rangeland laboratory in 1936—the

deal was ultimate nixed due a Supreme Court ruling.[21]

Fortunately, as of 1936, rainfall,

range conditions, and the economy all began to improve. Numbers

of calves sold went up along with prices. In the depths of the

dust bowl and depression, 1934, JA cattle were sold at an

average of $10.63 per head. By 1937, that figure was $30.69.

During this period, too, the number of cattle sold (primarily

calves), climbed from a low of 4,234 in 1935 to a remarkably

robust figure of 9,9053 in 1939.[23]

Even as the cattle market improved, making serious headway on debts required land sales, which Ritchie undertook—not surprisingly—with great care. He describes a 1938 sale to Roy Ransom as consisting of 6,492.71 acres of “very rough and remote” land located “on the outside boundary of the ranch.” For this land, Montie received $3.50 an acre totaling $22,724.490. “We feel this to have been an advantageous sale for the Estate,” Montie reports.[24] This sale is consistent with Ritchie’s plan to sell lands that are marginal both in quality and location. Another more substantial sale was that of the so-called Puckett Lands. This was a section of 41,140 acres which had been sold by Hobart much earlier, but due to nonpayment had been repossessed by the ranch in 1931. Ritchie notes that this was almost entirely canyon country, a piece of land which they “probably . . . got the least benefit from on the whole ranch,” the sale of which “will in no way impair the value or interfere with the operation of the remaining lands as a cattle ranching unit.” The sale does, however, reduce the overall size of the JA herd by some 1500 head. The sale price of $5.75 per acre was a total of $236,555.00. In all, as historian Byron Price sums it up, Montie Ritchie from 1936-1939 “concluded thirteen [land] sales amounting to just over 65,000 acres, for a total of $353,750.”[25]

Such payments would go on in order to secure 66,000 acres through 1948. Montie writes the legatees: “it is felt to be of prime importance to keep up the payments on the principal and interest due the State of Texas for these lands as failure to do so might result in the forfeiture of these tracts by the estate which would be disastrous to the ranch.”[26] The Estate also took payment of $40,000 from the US Government for 1937 conservation work, including the building of fence and stock tanks. Once all expenses were paid, Montie explains, “a small surplus of $1,453.66 was left in cash while the ranch was the better off with 23 miles of new fence and 43 new reservoirs. A similar program is under way here” for 1938. Ritchie’s pragmatism in this regard speaks to the responsibility he felt as executor of the Adair estate to take every step to improve the financial situation of the Ranch.[27] In all, Ritchie made good progress against the Estate’s steep debt, which in 1940 would still be 1.3 million.[28]

Cornelia’s will names a

number of individuals left cash amounts ranging from $500 to

$250,000. Not surprisingly, these inheritors, mostly living in

England, were desirous of their payment. Over the years of

difficult financial circumstances, they waited. Some accepted

buy-outs while others held out for full amounts.

In 1938, the Ransom and

Puckett sales of land, in addition to paying some $45,000 toward

the estate’s debt, paid off the outstanding half of godson’s

Thomas Arthur Renshaw’s $100,000 legacy and 15% of the principle

of the other legatees, totaling about $100,000. An additional

sum was put aside for other debt retirements and legacy payments.[29]

Joan Royse is a noteworthy

case. Royse, a native of Dublin now living in England, was

Cornelia’s personal secretary. Their relationship was long and

deep. Royse traveled with Cornelia to the ranch many times,

among other destinations, and seems to have been a genuine

companion and confidant of Cornelia. In fact, in addition to

$50,000, Cornelia left her personal papers to Royse—papers

which, by the way, have never been recovered by researchers.

Ritchie made payments to

Ms. Royse when she was in desperate financial circumstances

during the 30s. He then seems to have lost track of her, making

efforts through third parties to locate her in 1946. He received

a report of her living in England in impoverished circumstances

in a shabby hotel at age 70. She writes him that it would be

“wonderful if there were some more money coming to me, these are

rather difficult times to manage in. Still if you had not paid

me my legacy before the war I don’t know where I should have

been!”[30]

In January of 1947, Joan was happy to receive a settlement for

67%, $33,500.

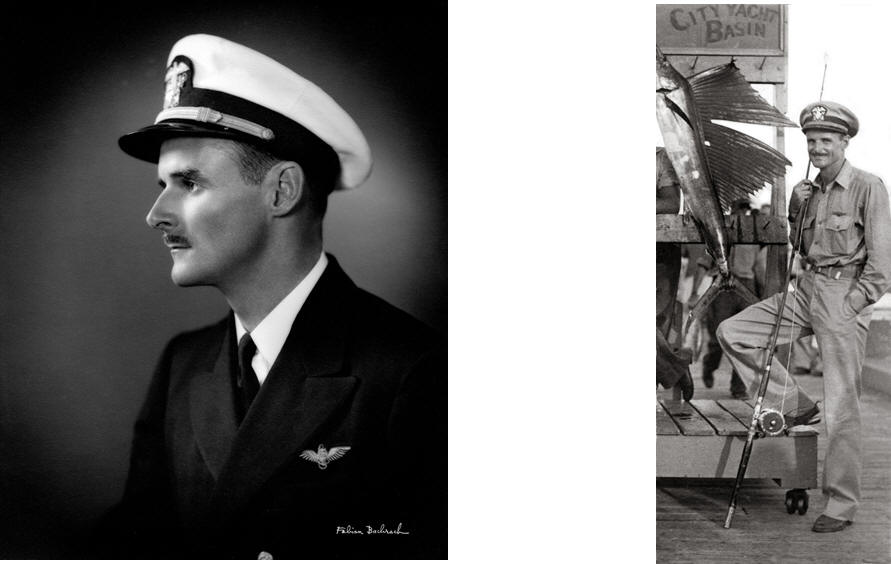

US Navy, ca. 1943; Florida, ca. 1955

It was this year, 1947,

that the estate was declared debt free and settled. During World

War II Montie Ritchie had served as an aviator in the US Navy,

flying cargo planes ferrying supplies.[31]

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, the war years had been excellent

for cattle prices. From the death of Cornelia Adair to the

settlement of her estate, the JA became leaner by 100,000 acres,

but Montie Ritchie—through determination, hard work, and good

luck -- saved the ranch.[32]

Ritchie was most certainly

a man of parts. Beyond running the JA, Ritchie excelled in

business. He was a leader in the Texas and Southwestern Cattle

Raisers Association and a director of the Continental Bank in

Fort Worth. Obviously an accomplished rider and roper, he

survived some horse wrecks. He was also an avid sportsman and

outdoor adventurer. He traveled to ski, fish, and to shoot birds

and other game. As a matter of expedience in traveling between

the ranch and business in Dallas and elsewhere, he bought a

plane and hired a pilot, whom he then had teach him to fly, and

this became a great pastime—and his contribution to the war

effort.

It bears mentioning here that

while initially of dual citizenship, Ritchie affirmed his US

citizenship at the time of his WWII service. Family and friends

attest that this service provoked an American patriotic spirit

that was quite fierce and he was known to disavow his British

origins. He once said, “My grandmother was not British, and I am

not British. I was born an American citizen and I fought in the

war for America.”[33]

with Betty (Barrell) Ritchie

There came marriage, the birth

of a daughter—subjects I pass over not to discount their

importance but because they fall outside my particular focus

tonight. He came along as a photographer on Arctic expedition of

Baffin Island in 1949. In addition to photography, he enjoyed

painting watercolors. Asked whether he produced his art in the

style of the impressionists he collected, he responded, “Yes,

but not as well.”[34]

And of course it is for his

efforts as a collector of art that we are here tonight to

celebrate Montie Ritchie. A man of refined taste, Ritchie once

described himself as having been a collector of art all his

life.[35]

At a certain point, though, this collecting became a more

serious undertaking—particularly the impressionist and

post-impressionist collection featured here. By all accounts, he

viewed his collection not as investment but rather was motivated

by his love and appreciation of the beauty of the art he

purchased. JA Ranch records that I was able to examine suggest

that Ritchie began to collect—not surprisingly—at about the same

time that the JA began to operate in the black and after

Ritchie’s WWII service.

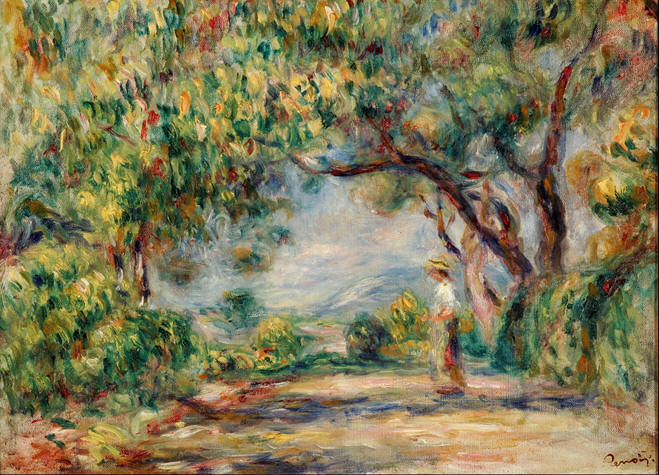

Renoir, The Wave Dixon Gallery & Gardens, Memphis, Tn.

Of the works of art that

ultimately went to the Dixon, the earliest confirmed date of

Ritchie’s purchase was that of Renoir’s “The Wave,” from Van

Diemen-Lilienfeld Galleries of New York, in 1949, two years

after the Adair estate was settled. Of the Dixon collection,

three works do not show Ritchie’s date of purchase, but after

“The Wave” in 1949, ten works—including the Cezanne and the

Seurat—were purchased in the 50s; six—including a Monet and a

Chegall—were purchased in the 60s; and one each in the 70s and

80s. Again where the provenance is specified, it is clear that

Ritchie bought from galleries like Arthur Tooth and Sons of

London and M. Knoedler & Company of New York. Such habits

suggest that the collector was not interested in the venture of

seeking out new artists, nor in engaging in competitive bidding

at Christie’s or other auction houses—but rather, it would seem,

a more leisurely and contemplative shopping about for works by

established masters that pleased his eye. Indeed in the catalog

published for this collection, Richard Brettell notes that

Ritchie was often able to borrow a work and hang it in his house

for some weeks before committing to the purchase.

The art collection grew and of

course appreciated. Its great financial value, ironically,

sadly, interfered with its pleasures for the collector. In

addition to being a substantial tax burden, the art was

attractive to thieves. And indeed this was a serious risk.

In 1970, a man named William

Van Noast Warren visited the JA Larkspur Colorado ranch house,

where a significant portion of the art collection adorned the

walls. A Harvard man and Denver businessman, Warren was also

member and vice president of the Denver Art Museum’s board of

trustees. Warren came to the Larkspur property in October,

ostensibly to speak with Montie Ritchie about “the development

of an island in Greece” as well as to see Montie’s collection.[36]

In other words, we might say, to case the joint.

Renoir, Les Colletes Dixon Gallery & Gardens, Memphis, Tn.

Ritchie departed for Texas the

next day and returned after four days. When he returned, he

found that the house had been broken into and his collection was

gone—including works by Renoir, Gauguin, Picasso, and and Talouse-Lautrec.[37]

In all, 16 works of art, paintings and bronzes, were taken.[38]

Warren traveled to New York

City. He presented himself, in false mustache and wig, as George

E. Parker, and attempted to sell Renoir’s “Les Colletes” and

Gauguin’s “Head of a Tahitian Woman” to an art dealer in the

city for an excellent bargain of $15,000 cash. The suspicious

dealer phoned the FBI, and agents arrested Warren in his hotel

room, where they found Picasso’s “Corrida” and Toulouse

Lautrec’s “Partie de Compagne.” Warren was charged with

interstate transportation of stolen property and released on his

own recognizance.

Picasso, Corrida Toulouse-Lautrec, Partie de Compangne

Additional charges were filed in

Colorado.[39]

Warren had stashed a number of the works in his house in Denver,

including five Degas bronzes and seven additional paintings by

Seurat, Gauguin, and others.[40]

The president of the museum board called the situation

“incredible.”[41]

Another museum spokesman said, “I can’t believe it’s

our Mr. Warren. He’s

such a nice man, and he’s

interested in art.” At trial, Warren pled

insanity—specifically, what was termed “toxic insanity” stemming

from prednisone he took for his asthma.[42]

The drugs, defense argued, led Warren to have dissociative

periods or fugues during which he had memory blackouts.

Prosecutors pointed out evidence of a crime complex in nature

and extended in duration, evidence of a clear mind at work. The

jury rejected the insanity plea and found Warren guilty.

A Colorado newspaper article

notes that Ritchie “has been known to avoid publicity, feeling

that such attention might endanger his collection.”[43]

True or not, it seems quite possible that the incident played a

role in prompting Ritchie to consider making other arrangements

for his collection. Still, this did not happen overnight.

Montie Ritchie with "Will Rogers" ca/ 1936

Montientie Ritchie in 1976 placed

much of his art in an arrangement called the “Cornelia Wadsworth

Ritchie Bivins Works of Art Trust.”[44]

The instrument reveals in part the statement that Ritchie made

the arrangement “in consideration of the love and affection

which I have for my daughter.”[45]

In the 1980s, it was decided that the Works of Art Trust still

had the family on “dangerous ground” with the Revenue Service.

Various solutions were proposed. One expedient was the

resignation, in 1982, of Montie Ritchie as co-trustee.[46]

Another was the loan or rental of artworks to other entities.

By 1989, elements of Ritchie’s

collection appeared at the Dallas Museum of Art, on anonymous

loan.[47]

Richard Brettell, whom the DMA hired in 1988, had visited

Ritchie at the JA early in his tenure. By 1992,

The Dallas Morning News

reported that the DMA was “near agreement on a joint

gift-purchase of a major collection of . . . paintings” from Mr.

Montgomery Ritchie, West Texas Rancher. But all was not well. A

newspaper editorial made an impassioned plea that the City

Council grant the $900,000 to the museum essential to maintain

its new expansion. This financial crisis, it seems, was the

ultimate cause that put a cramp in the agreement on the part of

museum’s foundation board to acquire the Ritchie collection.

What Brettell hoped would be a major coup was not to be.[48]

Unidentified Cowboys and Ritchie, ca. 1950

On the occasion of the 100th

anniversary of the JA, Montie Ritchie’s had this to say: “Nobody

or no organization succeeds alone in this world so the fact that

we are able this year to celebrate our 100th birthday

is due, in large part, to the wonderful, loyal, men and women,

leaders who worked for and with us, men of imagination, men of

skill, men of courage, men who braved the elements day or night,

men who took pride in their craft, loved their horses and

understood their cattle and were eager to enhance the reputation

of the JA and proud to be a part.”[49]

Despite his generosity in sharing credit, it is no exaggeration

to say that Montgomery Harrison Wadsworth Ritchie saved the JA

Ranch. In so doing, Montie Ritchie preserved a legacy. I wish to

suggest in my conclusion here that his desire to save the JA is

related to his later art collecting, which is of course what

brings us together here tonight. I have little to back up this

analogy except my own sense of these matters, and I don’t wish

to be either trite or pretentious in suggesting the comparison,

but it seems to me that a large historic cattle ranch and a

collection of fine art have things in common. Both things

demonstrate the work of collecting elements which must be

carefully chosen, disposed of, or retained—carefully cultivated,

framed, maintained, displayed, or perhaps kept unseen. Both

things have such a beauty that they must be a delight to behold,

but their magnitude is such that their scale or import goes

beyond the words to express. Both are things legally owned but

which carry a significance that

cannot be owned but

which must be—deserve to be—preserved and curated. We might do

worse than to think of both projects as acts of stewardship.

Montie Ritchie ca. 1955

Montie Ritchie intrigues me because he was simultaneously a man

of the ranch and a man of the city, new world and old, Cambridge

and the JA, cattleman and art connoisseur. But in that sense he

was part and parcel of what the JA always was, a partnership of

Goodnight and Adair, frontiersman and financier, Texas and

Britain—the JA is a fine example of the way in which the

Panhandle has always been a surprisingly cosmopolitan place even

as it is a place well off the beaten track. We should

all—regardless of our circumstances—aspire to be both worldly

and provincial, with one foot on the land and the other in the

library. And finally, just to touch on CSAW, this too is what I

hope that the Center for the Study of the American West can

demonstrate: the study of our western regions that is also

always mindful of our place in the larger world.

Click on brand to link to another ranch's

information.

Return to Ranches.org

[1] Adair to Hobart, 1

Feb. 1916. William Green Files.

[2] “At the time of the

division [with Goodnight] in 1887, Ledger “B” shows that the

JA Ranch owned 340,889

acres. The Tule Ranch contained 180,639 acres and the

contract of sale states that there were 140,000. The sum

total owned, then, was 660,528 acres. Taking the data of the

land leased and unleased which was given on the map of the

Tule Ranch as 274,154 acres and the leased and unleased land

given on the map of the JA Ranch as 335,520 acres and the

65,000 acres leased land in the Quitaque Ranch and adding to

these the 660,528 acres owned, it will give 1,335,202 acres

grazed by the combined interests of Adair and Goodnight at

one time.”—Harley True Burton, p. 59. At the time of

Burton’s writing (1927, under Hobart and Coke), he reports

of the ranch: “The total acreage is three hundred

ninety-seven thousand eight hundred acres”--397,800 acres

owned ca. 1927. So this would include the 140,000 acres lost

in the split with Goodnight. Tule Division was 170,000 acres

according to another source (https://cdn.loc.gov/master/pnp/habshaer/tx/tx1000/tx1058/data/tx1058data.pdf).

[3] Jane Pattie, “Montie

Ritchie: The Man and His Legacy—the JA Ranch.” The

Cattleman, March 1993, p. 30.

[4] Jane Pattie, “Montie

Ritchie: The Man and His Legacy—the JA Ranch.” The

Cattleman, March 1993, p. 32.

[5] 10/31/30 letter

Clinton Henry to JEH, Haley Library Correspondence Files.

[6] Montie Ritchie “Reel

1,” SW Collection, JA Papers, box 150, folder 30.

[7] “Reel 1” 2-3.

[8] “Reel 1” 4.

[9] B. Byron Price,

“Surviving Drought and Depression: The JA Ranch in the

1930s,” Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum (2002), 6.

[10] LOC, JWW to William

Greenough, April 29, 1933. Box 33.

[11] JA Box 11, Folder

23, letter to Mrs. Eliot, July 10, 1933.

[12] JEH II B, Hobart

Correspondence File, Hobart to Haley, 25 Jan. 1935. Haley

Library.

[13] JA Box 14, Folder

50, Round Robin Letter, June 12, 1935. Southwest Collection.

[14] B. Byron Price, 8.

[15]

JEH II B, Clinton Henry Correspondence File, Clinton Henry

to Haley, June 29, 1935. Haley Library.

[16] JEH II B, Clinton

Henry Correspondence File, Haley to Henry, 8 Sept. 1935.

Haley Library.

[17] JEH II B, Clinton

Henry Correspondence File, Haley to Henry, 8 Sept. 1935 and

Henry to Haley, 11 Sept. 1935. Haley Library.

[18] Jane Pattie, 33.

[19] Reel 1, 4.

[20] “Reel 1” 4.

[21]

Cited by Byron Price. I looked at this material at SW

Collection and found mention but not the details.

[22] Quoted by B. Byron

Price, p. 2.

[23] JA Box 146,

Folder 13, Round Robin Letter, Fourth Quarter 1938.

Southwest Collection.

[24] JA Box 146, Folder

13, Round Robin Letter, Third Quarter 1938. Southwest

Collection.

[25] Byron Price, 8.

[26] JA Box 146, Folder

13, Round Robin Letter, Third Quarter 1938. Southwest

Collection.

[27] JA Box 146,

Folder 13, Round Robin Letter, Second Quarter 1938.

Southwest Collection.

[28] Price,

“Surviving Drought and Depression,” 9.

[29] JA Box 146, Folder

13, Round Robin Letter, Fourth Quarter 1938. Southwest

Collection.

[30] Letter, Royse to

Ritchie, 15 Dec. 1946. Box 146, Folder 16. Southwest

Collection.

[31] One story has it

that Ritchie flew the ornate silver-mounted saddle, made in

Nevada, that Admiral William F. Halsey intended to mount in

his victory parade in Japan.

[32] Montie eventually

became sole owner of the JA, with 325,000 acres and 15,000

cattle.—says Byron Price. Question of sole ownership

disputed.

[33] Quoted in

Dorothy Abbott McCoy, “Montgomery Harrison Wadsworth ‘Montie’

Ritchie,” Texas Ranchmen, (Austin: Eakin Press, 1987), 112.

[34] Pattie, 47.

[35] Jane Pattie, “Montie

Ritchie: The Man and His Legacy—the JA Ranch.” The

Cattleman, March 1993, p. 47.

[36] Morris Kaplan,

“Art Theft Defendant Pleads Insanity.” New York Times, Jan

5, 1971.

[37] Kaplan.

[38] Duncan Pollock,

“FBI Makes Arrest in Stolen Art Case.” Douglas County News,

Oct 22, 1970.

[39] Duncan Pollock.

[40] Duncan Pollock.

[41] Duncan Pollock.

[42] Morris Kaplan.

[43] Duncan Pollock.

[44] “Petition to

Resign and for Discharge as Trustee Application for

Appointment of Successor Trustee.” 1982. Southwest

Collection, JA Papers, Box 145, Folder 17.

[45] Twenty-one works

were placed in trust in ½ or full interest. Some of these

works would later become part of the Dixon acquisition of 22

works.

[46] Ibid and Letter

Nov. 18, 1981 “Re: Works of Art Trust,” Box 145, Folder 17.

[47] Janet Kutner,

“DMA Acquiring Major Collection,” Dallas Morning News, 29

April 1992.

[48] Ann Zimmerman,

“Crisis at the DMA,” Dallas Observer, 14 May 1992, p. 17.

[49] Montie Ritchie,

“Famous JA Ranch Celebrates One Hundred Years of History,”

The Cattleman, 1976, p. 64.

[i] Adair to Hobart, 1 Feb. 1916.

William Green Files.