NATIONAL BANK OF COMMERCE

The National Bank of Commerce, located in the O'Brien Building at 5th and Polk

In 1917, Will O'Brien purchased the

National Bank of Commerce from a man named Sullenberger, when he moved from

Hereford to Amarillo. In 1922, it

was merged with City National Bank and T.E. (Tom) Durham was elected president

with Will O'Brien chairman of the board. The

bank remained in the O'Brien Building at 5th and Polk.

Shortly thereafter, O'Brien sold the bank to Durham on terms.

In May of 1928, Durham resigned as president. The newspaper gave ill health as the reason.

In order to protect the depositors who

had come to the bank because of

O'Brien, he took back the stock and again

became president. Before

he could get the bank back into shape, the depression hit and the bank

was effectively broke by 1931.

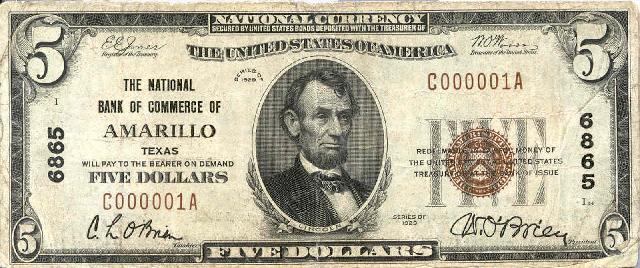

In 1929, the National Bank of Commerce, like many other banks, issued US currency signed by Will O'Brien as president and Cecil as cashier.

When the National Bank of Commerce experienced a run on August 8, 1931,

Will O'Brien worked out an agreement with Mr. Fuqua of the First National Bank

of Amarillo, and the other banks, under which the Amarillo banks would lend

O'Brien money to pay the Depositors. He

personally borrowed this money so the depositors in his bank would not lose

money. The other banks agreed to do

so in order to prevent runs on all of the Amarillo banks.

Gene Howe, publisher of the Amarillo paper wrote of the liquidation of

the bank in his "Tactless Texan" column on August 10,

The

passing of the National Bank of Commerce is something to be regretted, but there

is something might fine and splendid about the way it was done.

It would have been mighty easy for certain folks to have got from under

and have left it to sink, but instead of doing this they stood by the ship.

Howe praised O'Brien and the other officers of the bank, further saying,

They

dug down deep into their socks and put up their personal and private collateral

so that their friends and thus customers and the public in general would not

suffer any loss. It's a pretty good

idea to do business with men you know to be honest and honorable and square

shooters.

Howe attributed the

guarantee to three of the officers, but only O'Brien guaranteed the note.

| In negotiating collateral for the loan to O'Brien, the other three

Amarillo banks took all of the loans. However,

they required more collateral from O'Brien as they gave some of the National

Bank of Commerce's loans no value. In putting up everything he had as additional collateral, O'Brien

told the bankers that any of the collections from the valueless loans would not

be applied against his loan with the banks. Will's son Cecil collected loans for several years and paid

the collections on the notes to the other banks. |

When several of the larger

"worthless loans" turned out to be worth something, the three Amarillo

banks changed their mind and asked that the income from them be paid on the

note. Will O'Brien felt they were going back on their word. Their

relationship deteriorated and the banks threatened to foreclose on the loan,

which had been paid down to something over $100,000--a fraction of the original

amount. The depression worsened and the three banks were in desperate need

of liquidity. They called O'Brien in and told him, We need the money and we need

it now. We are going to have to

foreclose on your oil properties and other assets."

He owed the banks something over $100,000, which was a great deal of

money.

O'Brien negotiated a reduced payment with them, but said, "If I pay you off, the uncollected notes belong to me." They would not agree to this, wanting the payoff and the uncollected notes.

Will O'Brien called his friend and business associate Joe Perkins, from

Wichita Falls, and Perkins bought all of O'Brien's notes from the banks at a

discounted price. O'Brien had to

mortgage everything he and his children owned to guarantee the loan.

Perkins gave O'Brien eighteen months to pay the note off and O'Brien was

able to do it.

An interesting aside is that Exie O'Brien felt great anguish about the run on the bank because the day before the run she had told Mrs. Mathis, who lived across the street, that Will was having some financial problems. She always felt that Mrs. Mathis had gossiped around and in that way the run was started.